Cosmic string research

In the summer of 2019, I worked with Ken Olum at the Tufts Institute of Cosmology to study the properties of smooth cosmic string loops. I began the summer running computational simulations of cosmic strings and later transitioned to working on a mathematical proof. Below is an explanation of cosmic strings (warning: a bit dense) and a brief summary of my research.

Cosmic strings

(extracted from this excellent description by Alejandro Gangui)

I. Topological defects

On a cold day, ice forms quickly on the surface of a pond. But it does not grow as a smooth, featureless covering. Instead, the water begins to freeze in many places independently, and the growing plates of ice join up in random fashion, leaving zig-zag boundaries between them. These irregular margins are an example of what physicists call “topological defects” - defects because they are places where the crystal structure of the ice is disrupted, and topological because an accurate description of them involves ideas of symmetry embodied in topology, the branch of mathematics that focuses on the study of continuous surfaces.

Current theories of particle physics likewise predict that a variety of topological defects would almost certainly have formed during the early evolution of the universe. Just as water turns to ice (a phase transition) when the temperature drops, so the interactions between elementary particles run through distinct phases as the typical energy of those particles falls with the expansion of the universe. When conditions favor the appearance of a new phase, it generally crops up in many places at the same time, and when separate regions of the new phase run into each other, topological defects are the result. The detection of such structures in the modern universe would provide precious information on events in the earliest instants after the Big Bang. Their absence, on the other hand, would force a major revision of current physical theories.

II. Symmetry breaking

There are four physical forces in nature: the gravitational, strong, weak, and electromagnetic forces. At the very instant of the Big Bang, when energies were at their highest, it is believed that these forces were unified in a single, all-encompassing interaction. As the universe expanded and cooled down, first the gravitational interaction, then the strong interaction, and lastly the weak and the electromagnetic forces would have broken out of the unified scheme and adopted their present distinct identities in a series of symmetry breakings.

The standard mechanism for breaking a symmetry involves a hypothetical field (loosely analogous to a magnetic or electrical field) called the Higgs field, named for Peter Higgs of the University of Edinburgh and pervading all space. As the universe cools, the Higgs field can adopt different ground states, also referred to as different vacuum states of the theory. In a symmetric ground state, the Higgs field is zero everywhere. Symmetry breaks when the Higgs field takes on a finite value. By suitably linking the Higgs field to other fields, the theoretical physicist can arrange that the transition from one vacuum state to another can induce a loss of symmetry among other interactions in a theory.

In 1976 Thomas Kibble of Imperial College, London first saw the possibility of defect formation when he realized that in a cooling universe, such a phase transition would not necessarily proceed in an orderly fashion. Rather, there would appear uncorrelated domains-separate regions in which the Higgs field adopts different values-because places sufficiently far apart would not have had enough time to “communicate” among themselves. The Higgs field in one region would have no way of knowing what the Higgs field in another is doing. As these regions began to merge, Kibble pointed out, it would not always be possible for the Higgs field to be in the same vacuum state everywhere.

The nature of the defects that form depends on the symmetries of the Higgs field itself. For example, the Higgs field may have a choice of two possible states to fall into. In this case, when regions that have taken opposite choices run up against each other, the boundary is marked by a structure called a domain wall, in which the Higgs field is obliged to pass through zero, creating a localized region where the vacuum state is one of unbroken symmetry. The domain wall is a microscopically narrow region trapping what physicists call a false vacuum, as distinct from the true vacuum on either side. The false vacuum ought not to exist, but does so because the geometry of the Higgs field does not allow it to disperse.

III. Cosmic strings

Domain walls are not a good thing for cosmology: They are huge, massive and hard to get rid of. Fortunately, a more likely and perhaps even beneficial possibility is a Higgs field with circular symmetry, meaning that its ground-state value can be represented by a point on the circumference of a circle. When domains of broken symmetry form, the choice the Higgs field makes in each one can be marked by an arrow pointing in any direction from 0 to 360 degrees. In this case, when mismatched domains come together, the Higgs field adjusts so as to concentrate the discontinuity into a line rather than a wall. This is a string defect, an incredibly thin filament of false vacuum. So-called Grand Unified Theories, which aim to unite the strong interaction with the already unified electroweak force, tend to contain Higgs fields that produce these cosmic strings.

Proving that smooth string loops will decay

I worked with a mathematical abstraction of cosmic strings where they are treated as objects with zero thickness (in reality, the strings are thinner than the width of an atom, so zero is a fair approximation for many cases).

Cosmic strings can have features called “cusps” and “kinks”. A cusp is where the string doubles back on itself, forming a point (the point temporarily moves at the speed of light). A “kink” is a sharp bend in the string.

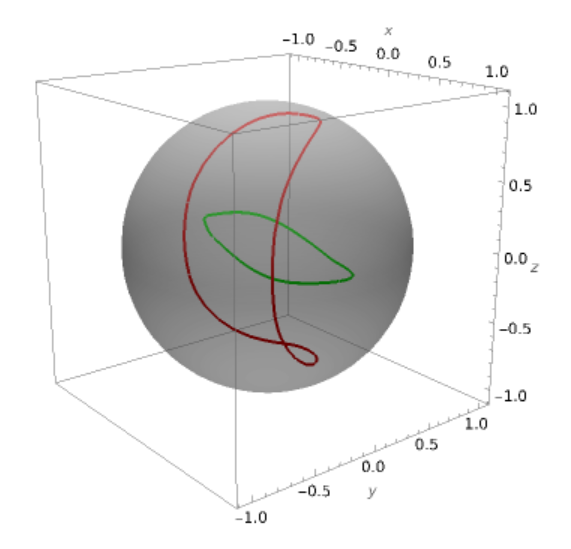

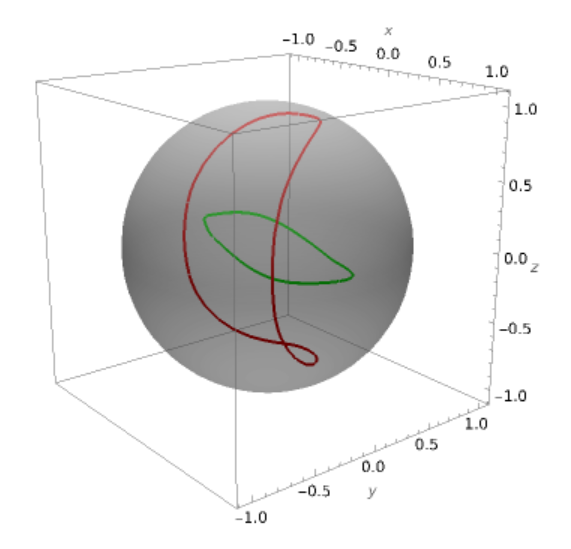

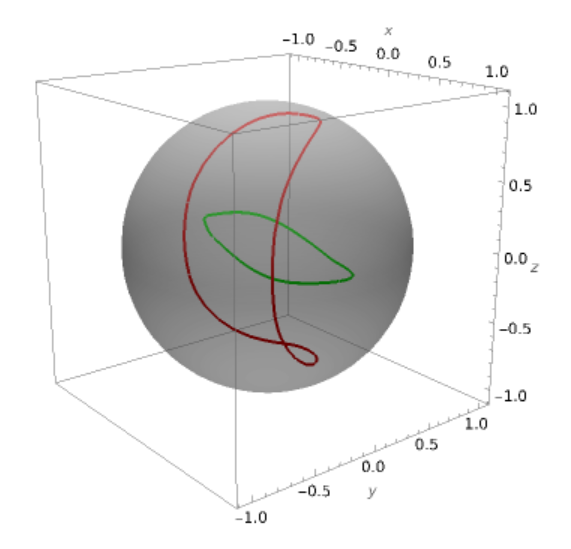

When a long string intersects itself, it will break off a small loop, leaving a kink behind in the original string. It is predicted that the remaining cosmic strings in the universe are mostly loops. I studied a subclass of these loops which have no cusps or kinks. The shape of the loop can be described by two 3D line functions, called a’ and b’, which are time and space derivatives of the string. These functions, projected onto the unit sphere, integrate to 0 over their entire length. Where the a’ and b’ functions intersect one another on the sphere, there is a cusp in the string. When there is a discontinuous jump in one or the other, there is a kink in the string.

Initially, I examined a specific loop of my advisor’s design that had no kinks or cusps. Cosmic string loops oscillate with a certain period, and if they self-intersect during this period, they will break into smaller loops and eventually disintegrate. While running simulations of it, I saw that this particular loop intersected itself in this way, and it seemed that the behavior could not be avoided by tweaking the string parameters. We were not able to find a similar loop that did not self-intersect, and visual inspection of a’ and b’ hinted that this problem may be unavoidable in general. My research advisor reached out to others and eventually found a different loop that is stable, but it had a fundamentally different formation. We decided to try to prove that all loops of our type of configuration would intersect themselves before they could complete a full oscillation.

We were unable to complete a rigorous proof by the end of the summer, although we did verify several special cases. Looking at the bigger picture, the work we did was not necessarily the most groundbreaking or influential, but it was my first time working on a problem that nobody had attempted before and actually getting some results out of it.

← back to jason-chadwick.com